close

Lazy Bracket Picker

Making NCAA bracket pool picks with Python

code ProgrammingI’ve participated in NCAA March Madness bracket pools since I was in fifth grade, with decent success over the years. However, I’ve recently found it more difficult and tedious to pick “good” brackets, as my free time (and level of interest) for keeping up with the wide world of sports has waned. However, I still enjoy the annual tradition that brings family and friends together, and the games just aren’t nearly as fun to watch without a reason to care about who wins (since Penn State generally isn’t in any of them).

When this year’s tournament rolled around, I found the bracket submission deadline quickly approaching due to a busy week at work, and I knew that I didn’t have more than thirty to sixty minutes to commit to picking my brackets. Rather than spend that time cramming stats in an attempt to make educated guesses (as I have for the last few years), I decided to try a different approach that might more easily be applied in future years: a quick and dirty Python script.

With some Googling, I was able to pull together a table of round by round odds by seed, based on historical results, as well as specific team odds for this year’s teams. Using these odds individually, and in combination, I elected to simulate games with what amounts to simple weighted coin flips.

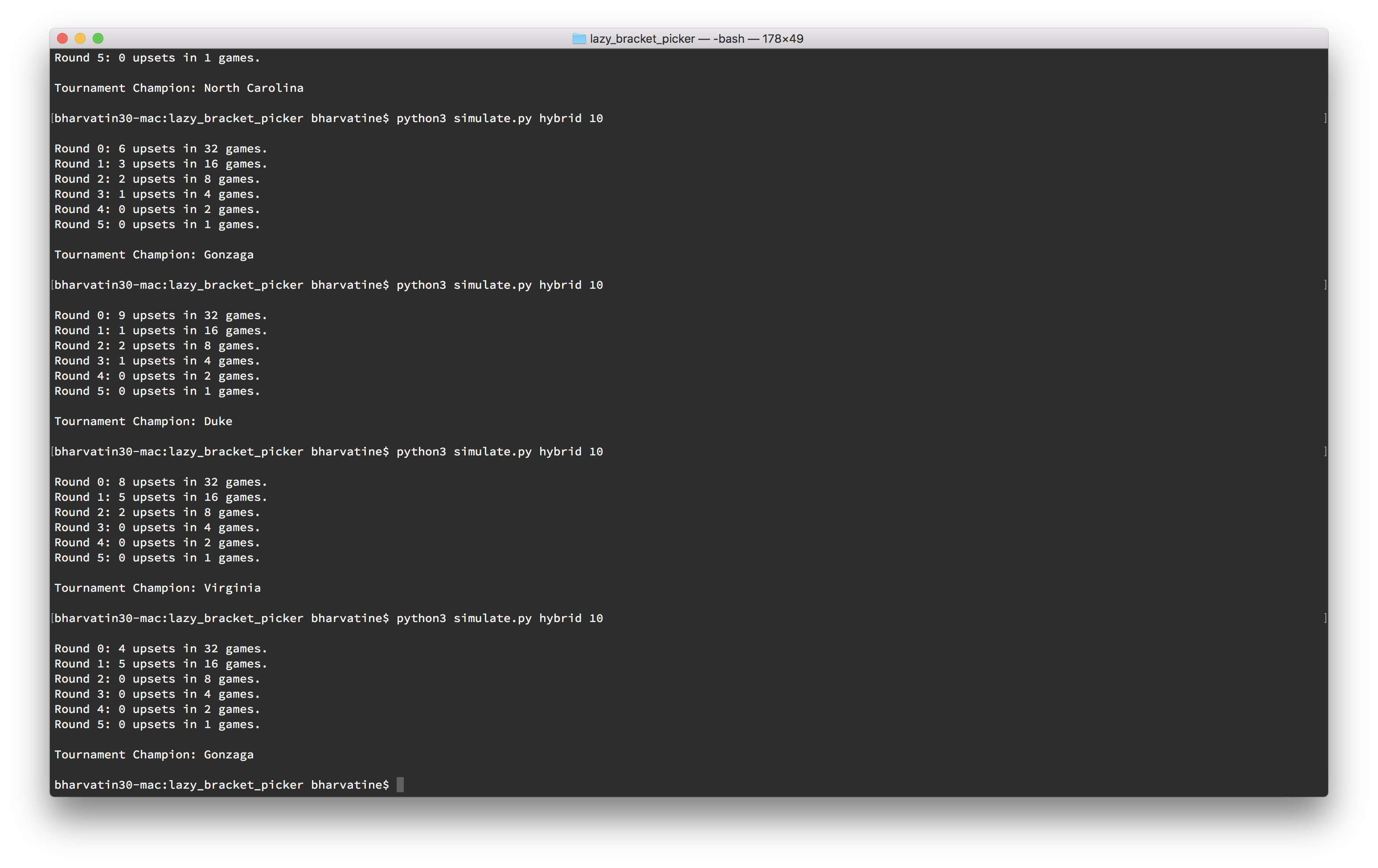

The program accepts commands of the format simulate.py [seed|team|hybrid] [# of simulations]. The first argument indicates the odds to use for the simulations. Seed-based uses the historic probability of a given seed reaching a given round of the tournament, team-based uses AccuScore’s probability of a given team reaching a given round of the tournament, and hybrid simply blends the two. The second argument indicates how many simulations (weighted coin flips) to run for each game in the tournament.

Intuitively, larger numbers tend to follow the selected odds more closely, while fewer simulation will introduce more “randomness” into outcomes. I found that 10-20 simulations per game generally yielded a nice round-by-round distribution of upsets roughly in line with historical outcomes (since 1985, when the tournament field was expanded to 64 teams):

| Rounds | Average | Least | Most |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Round | 6.1 | 2 (2007) | 10 (2016) |

| Second Round | 3.7 | 0 (3 times) | 8 (2000) |

| Sweet Sixteen | 1.7 | 0 (5 times) | 4 (1990) |

| Elite Eight | 0.5 | 0 (10 times) | 2 (2 times) |

| Final Four | 0.2 | 0 (23 times) | 2 (2014) |

| Total Upsets | 12.7 | 4 (2007) | 19 (2014) |

With the script finished quickly enough to leave some time for fiddling, I just slammed around in Terminal until I saw an upset distribution that I liked and a champion that I could live with. I also applied a little strategic thinking to avoid scenarios with champions that homers in my pools were likely to select (Duke, North Carolina, Purdue, and Michigan in one; Kansas and Wisconsin in the other).

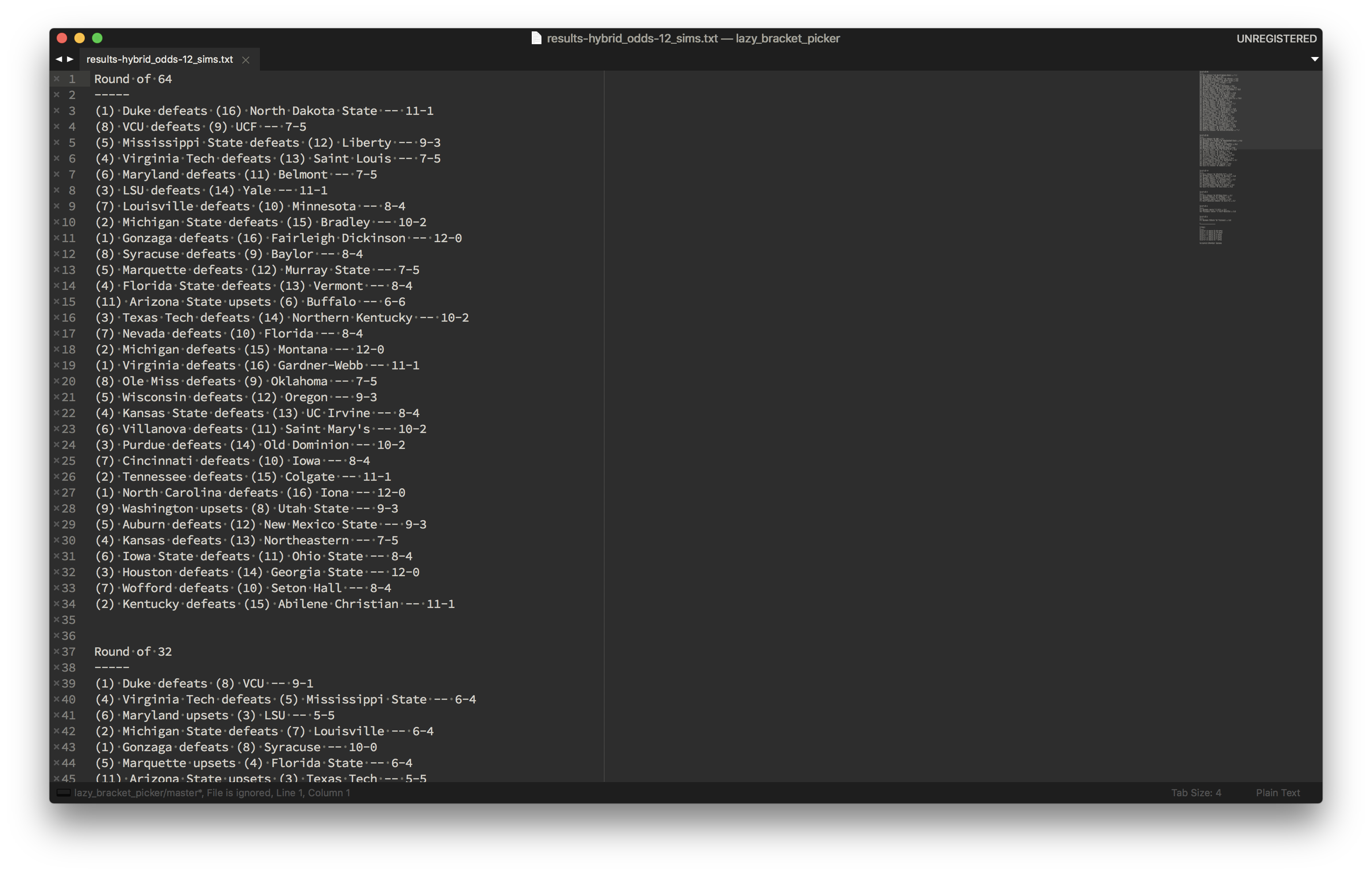

Going all the way back to my first bracket (in fifth grade), I’ve always been an irrational sucker for Gonzaga and Xavier… Content with my picks, and ready to fill out my bracket, I pulled up the human-readable exports that the script had generated and saved as I ran scenarios:

I’m crossing my fingers for success, but, either way, I’ve accomplished my goal of a low-overhead way to participate in some friendly trash-talking and generate personal interest in the games. If you’d like to pick your own lazy bracket, you can check out the source code and documentation here. Enjoy!

April 9, 2019 Update

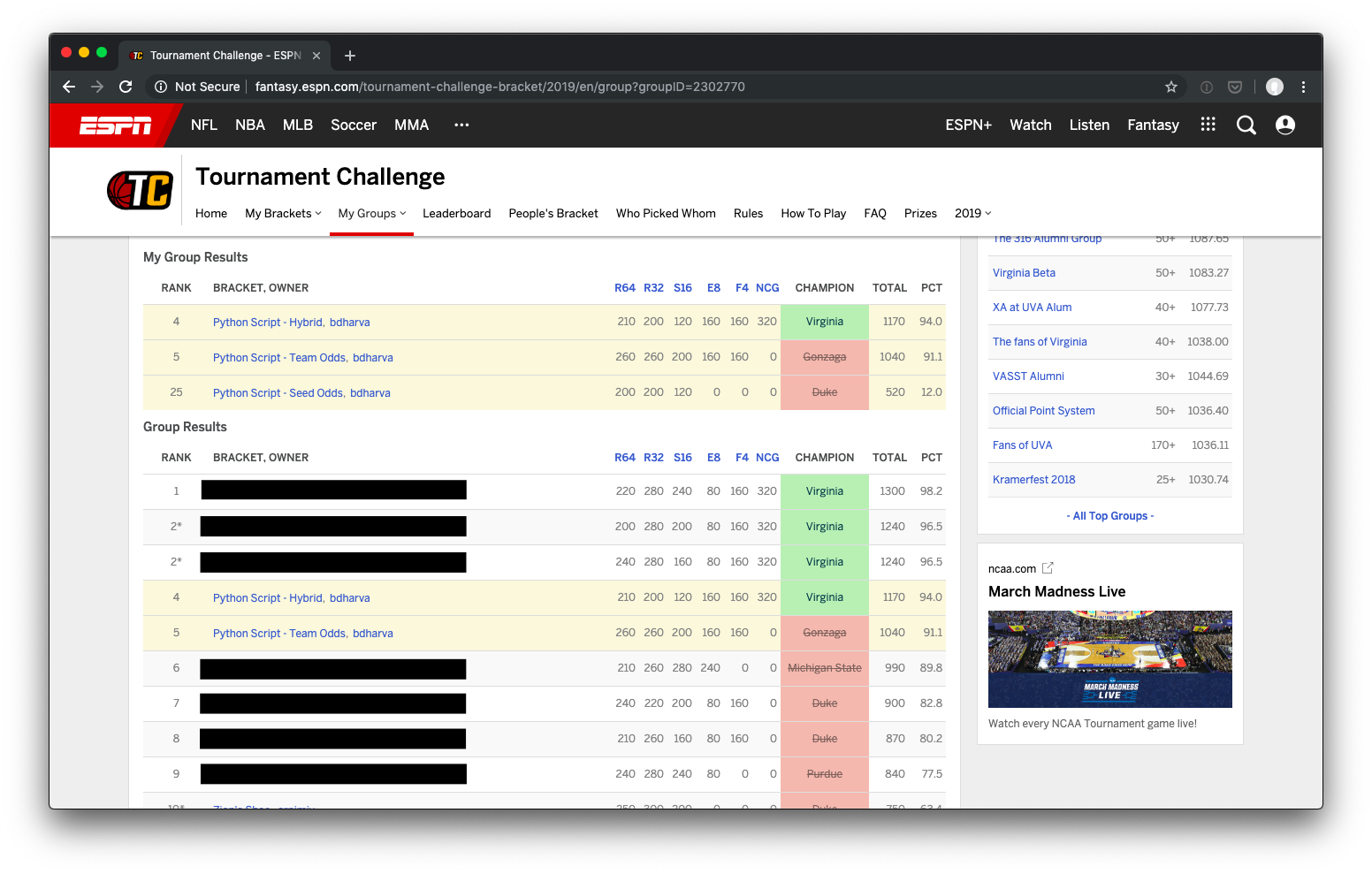

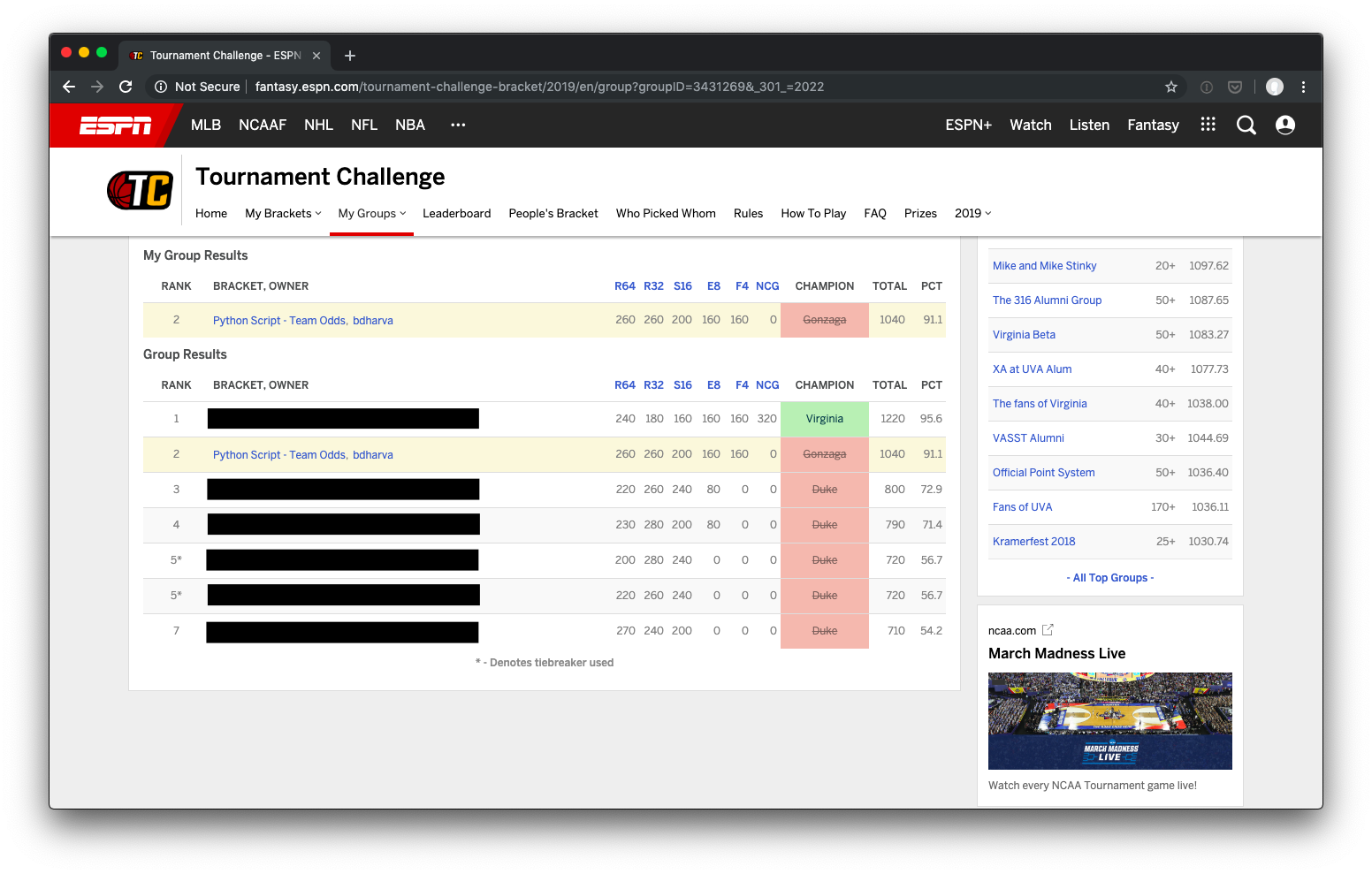

Things turned out surprisingly well! I made three entries in a 25 bracket pool, and another in a seven person group. The historic seed-based odds fared the worse, finishing dead last in the large group and in the 12th percentile of all brackets submitted on ESPN. I used team odds bracket in both groups, finishing 2nd in the small one, 5th in the other, and at in the 91st percentile overall. While my hybrid odds bracket just edged it out (4th place, 94th percentile), it only surged ahead with a correct pick for the national champion. With a few different bounces late in some very close games, the team odds bracket would’ve finished even stronger.

Following up on this surprising success, I intend to run a more rigorous analysis of how varying input parameters would’ve fared this year, as well as how “typical” my results were given my selected parameters. It will be interesting to see (with a couple thousand more simulations) whether my brackets were lucky outliers or in the meat of potential outcome distributions.